Go here to find out more:

staceygreenway.wordpress.com

Wednesday, April 14, 2010

Wednesday, November 25, 2009

Lyle McDonald on Dietary Cholesterol and Fat and their Impact on Blood Cholesterol

"1. Cholesterol intake per se tends to have a minor effect on total blood

cholesterol. first and foremost, your liver makes more cholesterol on a

daily basis (anywhere from 1.5-2 grams/day) than you would generally eat

(well, 2 grams per day of cholesterol would be 7 whole eggs). On top of

that, liver cholesterol production adapts to your intake. So when you

eat more cholesterol, the liver typipocally downgrades its own

cholesterol production ; when you eat less cholesterol, the liver

upregulates its own cholesterol. This is all basic physiology, in any

decent textbook.

1a. However, there is a wide range of difference in how people respond

to dietary cholesterol per se. There are both hypo and hyperresponders

meaning that some people are sensitive (in terms of total cholesterol

levels) to dietary cholesterol intake. But certainly not all.

2. The bigger issue in blood cholesterol intake has to do with fatty

acid intake NOT cholesterol intake. For example, most saturated acids

tend to raise blood cholesterol levels by affecting liver metabolism

(differently than dietary cholesterol intake does). There are

exceptions, such as stearic acid which is saturated but doesn't affect

blood cholesterol intake. Monounsaturated fats (olive oil, which is

oleic acid, being the primary one) has a neutral effect on blood

cholesterol levels. Polyunsaturated fats (w-6 and w-3) have cholesterol

lowering effects, in general.

3. Now, *in general* foods high in cholesterol are also high in

saturated fats but this is not always the case. Even lowfat foods such

as chicken and lowfat fish contain cholesterol because it is part of the

cell membrane. Eggs contain both cholesterol and saturated fat

(although there are more polyunsaturated fats in eggs than most people

realize, you can check the USDA database to check that). Same with

fatty cuts of red meat: both cholesterol and saturated fats are present

(note that red meat actually contains mostly oleic acid, and a good bit

of the saturated fat is stearic which I already mentioned doesn't affect

blood cholesterol negatively). At the other extreme, there are foods

like coconut and palm kernel oil which are highly saturated but contain

no cholesterol. So while the two are generally associated food wise,

it's not an absolute case.

4.Chronically high insulin levels (which can occur when you tell peope

to replace fats with carbohydrates, depending on their carb choices)

also affect blood lipid levels (insulin stimulates HMG-CoA reductase

which is the rate limiting enzyme for cholesterol synthesis in the liver

; high insulin also raises blood triglyceride levels which is an

independent risk factor for heart disease).

Ok, so what about eggs. The original backlash against eggs had to do

with their cholesterol content, because at the time cholesterol intake

was being blamed for high blood cholesterol levels, which we now know

has only a minor effect. That's part of why you'll hear the 'bull****'

on 'eggs raise blood cholesterol'.

But, you ask what about the fat content. Looking at the USDA database, a

whole egg is listed as having

Total lipid (fat) Gms : 10.020 10.4% 13.7%

OF which the following major fatty acids appear (there are trace amounts

of some others but I'm leaving them out).

Palmitic acid (16:0) Gms : 2.226

Stearic acid (18:0) Gms : 0.784

Oleic acid (18:1) Gms : 3.473

Linoleic acid (18:2/n6) Gms : 1.148 17.9% 23.4%

Ok, 2.2 grams of palmitic, which is a cholesterol raising saturated fat.

0.7 g of stearic acid, a neutral saturated fat.

3.4 g of oleic acid whith is neutral

1.1 g of w-6 which is a cholesterol lower polyunsaturated fat.

So of the 10 total grams of fat, 2.2 grams are negative in terms of

cholesterol, 4.1 are neutral, and 1.2 is positive.

Hardly the death in a white shell that they are made out to be.

So that's the basic gist of it.

Yes, excessive saturated fat has a negative impact on cholesterol.

For some people, excessive cholesterol can have an additional minor effect.

Yes, saturated fat and cholesterol tend to accompany one another but not always.

The rest of the diet (fiber, w-3/w-6 intake from other foods) has to be

taken into effect.

And that doesn't even bring the effect of exercise into the equation."

Tuesday, November 24, 2009

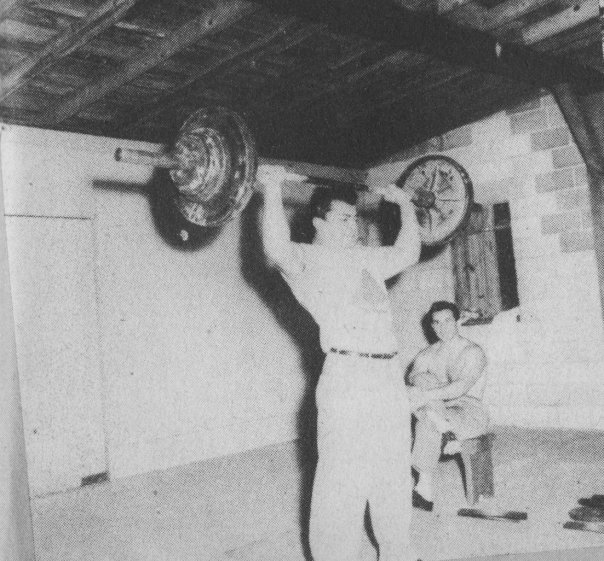

Brooks Kubik on the Press and Treating Lifts as "Skills"

Increasing the Press

by Brooks Kubik

In the old days, most men who lifted weights in a serious fashion practiced the standing press – and most of them were reasonably good at the lift. Let’s work together to bring that aspect of training back to the Iron Game. Make it a belated New Year’s resolution: “This year, I WILL get serious about my standing press numbers.”

Having said that, let’s discuss some basic points about getting started on the standing press and increasing your poundage in the lift. Here are twelve tips for lifters who are starting to re-discover the standing press:

1.) Practice Makes Perfect

There is a very precise pressing groove. You learn “the groove” through practice. To become a better presser, you need to press way more often than once a week or once every 10-14 days of heavy pressing. In the old days, Olympic lifters trained the exercise three, four or even five times a week. Personally, I think that four or five times a week would be excessive. But there’s nothing at all wrong with doing standing presses two or three times per week. In fact, many will find that it’s the best way to improve the lift.]

2.) Train Heavy

If you do high or medium rep sets in the standing press, you probably are not going to develop exactly the right groove for heavy presses. With light and medium reps, you use light weights, and with light weights, you can easily push “close” to the right groove, but not “in” the groove. Close only counts in horseshoes, folks. In lifting, your goal should be to make an absolutely perfect lift on every rep you do.

As noted above, the standing press requires you to develop a very precise pressing groove. In this sense, it is both a “skill” lift and a “strength” lift. You MUST train the lift with heavy weights and low reps in order to learn how to do it properly.

Think about how lifters train cleans and snatches. Do they do high reps? No. They do singles, doubles and triples. If you do higher reps in a “skill” lift your form breaks down and you actually teach yourself the WRONG groove.

3.) Select the Proper Rep Scheme

To use heavy weights, you MUST use relatively low reps. Anything over five reps is too many. Doubles, triples and singles are great. The 5/4/3/2/1 system is excellent. And remember, you don’t need to do 50 presses in every workout. a total of 7 to 15 presses is fine. (5/4/3/2/1 equals a total of 15 reps, which Bob Hoffman considered to be ideal.)

4.) Train the Lower Back

Always remember, the standing press builds works, trains and conditions the lower back. That’s one of the most important aspects of the exercise – indeed, it may be the MOST important aspect of the exercise.

But the other side of the coin is this: if you have not been doing serious work for your lower back, you are NOT ready to train hard and heavy on standing presses.

Unless your lower back is strong and well conditioned, the FIRST thing to do is to go on a specialization program for the low back. After six to ten weeks of concentrated lower back work, you will be ready for standing presses.

This is especially important for anyone who has been avoiding squats and training his legs with leg presses, hack machine squats, dumbell squats, wall squats or any other exercise that takes the lower back and hips out of the picture.

Ditto for anyone who does trap bar deadlifts as his exclusive lower back exercise. The trap bar deadlift is not as effective a low back builder as are deadlifts performed with a regular bar. It’s more of a hip and thigh exercise. Many lifters injured themselves by using trap bar deadlifts as their exclusive low back exercise, not realizing that it really does not work the low back as effectively as other movements. Then they hurt the low back doing squats, rows or curls, and wonder what happened.

Anyone who has been training with bench and incline presses (or dips), back supported overhead presses (or machine presses), leg presses and trap bar deads -- a schedule I mention because it is highly popular and similar to that used by many modern lifters – should devote serious attention to training his lower back before he tackles standing presses. Such a lifter may have fairly strong shoulders and triceps, and may THINK that he can go out and start doing standing presses with BIG weights. He can’t. His lower back will not be anywhere strong enough and well conditioned for serious work on the standing press.

Let me also note that one of the very best exercises for building STABILITY throughout the lower back and the middle of the body is the wrestler’s bridge. Try 3 sets of 30 seconds per set (with no weight) and work up slowly and steadily until you can do 3 sets of 3 minutes each. You won’t believe how much stronger and more stable you are when doing your barbell exercises. In this regard, don’t forget that I started to do bridging in the Spring of 2000, and by the Fall I had worked up to 12 reps with 202 lbs. in the “supine press in wrestler’s bridge position.” At about the same time, I hit a personal best of 270 in the standing press. Coincidence? I don’t think so.

If you ask someone to list a few good “assistance exercises” for the press, they’ll usually say, “dumbell presses, side presses, incline presses, push presses, jerks, upright rowing, etc.” – in other words they’ll think of “shoulder exercises” and different types of pushing movements. That’s lazy thinking. The shoulder, triceps, traps and “pressing muscles” get plenty or work from pressing. The most beneficial “assistance exercises” for the press are those that strengthen the middle of the body.

5.)

All of the foregoing points apply to training the waist and sides. Unless you already have been doing this, work hard on these areas for six to ten weeks BEFORE starting to specialize on the standing press.

With regard to the waist and sides, the big problem is the crunch. The exercise gurus who have promoted the crunch for so many years have done nothing but develop a generation of lifters who lack any reasonable degree of strength and stability in the middle of their bodies. Scrap the crunches. Replace them with bent-legged situps (with weight, 3x8-12), lying or hanging leg raises, heavy sidebends and the overhead squat.

The overhead squat?

Kubik, have you lost your mind?

No, not at all. The overhead squat builds tremendous strength and stability all through the middle of the body. It hits the inner abdominal muscles that lie BENEATH the “abs.” When it comes to strength and stability, these are the muscles that count.

And while we’re talking about core strength, let’s talk about the power wheel. Paul Anderson used a simple cart type of this apparatus, described in an earlier press article in IronMan.

6.) Start Your Day With Presses

Many lifters train their presses after doing heavy squats or heavy back work. That doesn’t work very well, because your lower back is tired and you are less stable. Do the presses first. That’s the way Olympic lifters did their training in the old days, and remember, those guys were all specialists in the standing press.

7.) Be Aggressive

Every single one of you can develop the ability to do a standing press in perfect form with bodyweight. I mean that. Dead serious. Every single one of you . . . bodyweight . . . in perfect form.

That should be your long-term goal.

For the younger guys, and for the stronger, more experienced lifters, bodyweight is just the beginning. Once you hit bodyweight, set your sights on 110% of bodyweight. When you can do that, shoot for 120% . . .

Anyone who can handle bodyweight in the standing press is STRONG!

Anyone who gets up to 130% is handling weights equal to some of the very best Olympic lifters in the world back in the pre-steroid days.

Norb Schemansky, in the 198-lb. class, handled 281 pounds. If you do the math you’ll see that Schemansky was pressing 142% of his bodyweight. These numbers show what a strong, determined man can achieve with years of proper, hard training.

8.) Try Cleaning for your Presses

Many lifters find they can press more if they clean the weight than if they take it off racks or squat stands, because the bar is better positioned for a heavy press. So learn how to clean, and try cleaning the bar before pressing it. You might find it adds a little more zip to your pressing.

9.) Dumbell Pressing

From Saxon to Grimek, from the beer halls of Austria to Davis, Hepburn and Anderson, many, many old-timers specialized in heavy dumbell pressing. And guess what? The best dumbell pressers usually turned out to be the best barbell pressers! You see, heavy dumbells are very hard to balance. To improve your overhead pressing, you need to do plenty of overhead pressing. Heavy dumbell exercises, however, are a tremendous assistance exercise for the standing press. Keep them in mind, and when your progress slows down, work them into your schedule. Harry Paschall used to swear by them; heavy dumbell pressing is one of the “secrets” in his 1951 classic, “Development of Strength”.

10.) Handstand Pressing

Another excellent assistance exercise for the standing press is the handstand press. Grimek used to do plenty of handstand presses and gymnastics work, and he became one of the best overhead pressers of his generation. Sig Klein used to specialize in handstand presses and tiger bends, and he managed an amazing record in the military press – a heels together, letter perfect military with 150% bodyweight. Paschall, who was good buddies with both Grimek and Klein, swore by the movement. Give them a try!

11.) Keep the Back, Abs and Hips Tight

For proper pressing, you need to “lock” your low back, abs and hips. Most lifters will do best if they also tense the thighs. The entire body must be tight and solid. Pretend you are doing a standing incline press without the incline bench. Your body must support the pressing muscles and the weight of the bar exactly the same as would an incline bench. (This is NOT to say that you lean back and try to press from a 60 degree angle or any similar foolishness. I don’t want you to lean back as if you were ON an incline bench, I want you to understand that your back, hips and abs have to give you that same level of support that a solid bench would provide.)

12.) Specialize for a While

The standing press is an exercise that responds very well to specialization programs. Try a schedule devoted to very little other than heavy back work, squats or front squats and standing presses. Remember, the great Olympic lifters of 30’s, 40’s and 50’s devoted almost all of their time to cleans, snatches, presses, squats and jerks, with a significant amount of their training being devoted to the press. They built enormous pressing power and tremendous all-round strength and power. You cannot do better than follow their example.

The foregoing tips will help anyone become not just a good, but an EXCELLENT presser. And remember one more thing – pressing is LIFTING. The standing barbell press is one of the most basic tests of strength ever devised. It has been a standard measure of a man’s physical power since the invention of the barbell. When you become a good presser, you can rightfully claim your place among the lifters of the past and present. Do it!

Thursday, November 12, 2009

The Why and the How, the Safety and Efficacy of Strength Training

Part One: Why Strength Train?

Often, physicians and medical professionals cite the benefits of regular, moderate physical activity, particularly the cardiovascular varieties (walking, jogging, biking and swimming, to name a few), but few emphasize the need to strength train. The reasons for this are many, the most likely of which are that cardiovascular training isn’t complicated, doesn’t require special equipment, and isn’t technique-dependent. Medical professionals likely feel that doing something is better than nothing when it comes to physical activity, and less hassle means, odds are, that patients will adhere to a given workout routine for the long term.

But consider that, as we grow older, our ability to carry out everyday physical tasks, such as climbing stairs or lifting heavy objects up and placing them overhead, decreases. Our quality of life depends on the presence of adequate levels of skeletal muscle, the muscle that attaches to our bones and transmits force along them to whatever is being lifted or pushed against, and the ability to recruit these muscles in an efficient, coordinated manner. Cardiovascular training (or “cardio”) does not significantly enhance the size or the quality of the muscles responsible for carrying out everyday tasks. Cardio can improve heart health, but so can strength training, which also greatly improves balance, coordination, strength, and flexibility, when programmed and executed properly.

But what is strength? Put simply, strength is the ability to generate force. Both increased neuromuscular efficiency (which has to do with the way the nervous system “talks” to the muscle) and an increase in size contribute to strength. Strength also depends on the ability of the body to store and quickly replenish energy for the muscles to do their work. When following a properly designed and executed strength training program, you enhance all of these abilities at once.

Part Two: How Do We Strength Train?

The general public regards any training that involves the use of free weights or some other means of external resistance as “strength training.” But while any resistance training program, by definition, must involve some means of applying resistance, strength and conditioning professionals mean something more specific when they use the label “strength training.” Here, it is being used to describe a systematic use of weights to enhance the muscles’ ability to produce force. Using a light weight to perform a large number of repetitions in the range of fifteen or more, for example, does not significantly improve strength because the muscles responsible for the movement are not being made to contract at or near their current maximum force potential. Heavier weights and fewer repetitions are needed in order to make that happen.

For a better understanding, we should conceptualize training in terms of stress and adaptation. When subjected to an unusual stress, our bodies adapt by becoming better at dealing with that stress. If we require our muscles to produce near maximal force by applying resistance to them, then they will respond with an increased force capacity the next time. Provided that we set aside adequate time and energy for recovery between training bouts, strength will increase in an uninterrupted, linear fashion for many weeks and months, if we continue to change the stress—i.e. use progressively heavier loads.

By contrast, using a light weight for a large number of repetitions will primarily enhance muscular endurance, which is a result of an increased ability by the muscle to handle waste products and to store energy, among other things. This is wonderful, but heavier loads utilized across fewer reps can provide a boost to muscular endurance as well (albeit through different mechanisms); and if either a lack of or a decline in strength is limiting you, then much of your time should be spent training in the heavier range anyway. And really, most of us aren’t as strong as we’d like to think we are.

On that note, loads that fall within the range of 75-85% of a person’s current ability to lift will achieve the desired effect. This will mean being able to perform between four and eight repetitions of an exercise before form begins to suffer. As far as exercise selection, we should opt for movements that recruit as much muscle as possible around as many joints as we can, so that a good deal of weight can be used. This should be done over a full range of motion, so that flexibility can be improved and maximum tension is placed on the muscles. Tension is what we’re after. Tension provides mechanical stress, and mechanical stress is what signals the muscle fibers to grow.

Furthermore, the closer these movements correspond to activities that we’ll be performing in the outside world, the more beneficial they’ll be to us. For this reason, and for those stated above, the barbell back squat, overhead press, deadlift and bench press will form the “backbone” of any effective strength training routine. Now, before anyone—man or woman—should balk at the idea of using barbells, I should explain why barbells are the ideal training implement versus dumbbells, resistance bands or cable machines, to name a few of the alternatives.

Compared to dumbbells, barbells accommodate our need to lift “heavy” weights better because they’re less cumbersome to wield and can be loaded using increments small enough to ensure continual, lengthy progress: whether positioned on our backs or in our hands, barbells are “easier” to handle and allow the trainee to utilize loads nearer to maximum, yet demand a tremendous amount of focus, coordination and stability. This is amply demonstrated by the effort it takes to move a barbell the distance covered by a full-depth back squat, for example. And while machines, cables and resistance bands are less cumbersome even than barbells, they do not require the same level of focus, coordination, stabilization and overall commitment that the barbell does, when supported by the muscles and all of the other skeletal components over the broadest range of motion that still permits good form.

Every workout should include some version of the squat, a pressing exercise and a pulling exercise, so that all of the musculature gets worked in a balanced fashion. For a novice, a full-body barbell routine performed three times a week will make the best use of the trainee’s recovery abilities and optimize his or her growth.

Safety and Efficacy of Barbell Training

Barbell movements, when performed under the watchful eye of an experienced coach, are absolutely safe. Heavy lifting in and of itself is no more injurious than any other rigorous physical activity, and given proper instruction and skillful coaching, heavy barbell training is, in fact, safer. Consider the fact that most folks who train do so without the benefit of an experienced coach or were coached by someone who may or may not have known the proper (i.e. safe) way to execute the movements. If care is taken by the trainee and coach to select loads that are within the current ability of the lifter, and if proper form is utilized, then the risk of serious injury is minimal to non-existent.

Young and old, male and female, dog and cat can safely train in the ways that I’m describing. Both groups will respond to training in much the same fashion, except that older trainees may need more recovery time between training sessions, making a twice-weekly training program more appropriate for some. Male and female trainees will adapt at comparable rates and for roughly the same amount of time on a linearly progressed training regimen.

The general public looks on fearfully at the use of heavy weights. Most believe that training of this kind is harmful to the back and joints. If the load selected matches the trainee’s current ability to lift it, then the muscles around the joints will be handling the load, not the joint surfaces or the ligaments. This is very important to understand. Muscles form a natural “organic brace” around each of the various joints, similar in principle to the orthopedic braces that doctors prescribe for use on patients with knee, ankle or elbow problems. Training these muscles in a balanced fashion around the joints and with the joints held in their mechanically sound anatomical positions makes for healthier joints, if anything. Again, proper weight training leads to healthier joints, not injured joints.

On the subject of youth and adolescent strength training, the National Strength and Conditioning Association (N.S.C.A) recently published an updated position statement that favors vigorous lifting practices, including but not limited to pure strength training of the type outlined above. The paper, entitled “Youth Resistance Training: Updated Position Statement Paper from the National Strength and Conditioning Association,” states:

In general, the risk of injury associated with resistance training is similar for youth and adults. There are no justifiable safety reasons that preclude children or adolescents from participating in such a resistance training program.

To elaborate, the authors note that several studies have found football, wrestling, and gymnastics to be substantially more injurious than resistance training, with the latter comprising only 0.7 percent of 1,576 injuries reported according to one prospective study. Further, the 2005-2006 High School Sports-related Injury Surveillance Study looked at 1.4 million injuries and determined that football had the highest rate of injury, scoring 4.36 injuries per 1,000 “athlete exposures,” as compared to only 0.0013 for resistance training and weightlifting (an Olympic sport). In fact, according to the N.S.C.A., the forces that young athletes encounter on the field or court are “likely to be greater in both exposure time and magnitude” as compared to those encountered while lifting properly.

Within the medical community, fear once existed that resistance training in general could stunt a young athlete’s growth or damage his or her growth cartilage, but to the contrary, the authors of this paper note that “there is no evidence to suggest that resistance training will negatively impact growth” and that “injury to the growth cartilage has not been reported in any prospective youth resistance training research study.”

The authors provide a ringing endorsement for the inclusion of resistance training in youth and adolescent training programs:

Youth resistance training can improve one’s cardiovascular risk profile, facilitate weight control, strengthen bone, enhance psychosocial well-being, improve motor performance skills, and increase ayoung athlete’s resistance to sports-related injuries.

Sunday, October 11, 2009

Words of Wisdom from Jim Wendler

(pic of Jim generally being awesome)

Here I’m paraphrasing comments that Jim Wendler made in his “Big” seminar, footage of which can be found on Youtube. He discusses the commonalities between all the programs followed by all the really strong, successful lifters:

1. They all bench, squat and deadlift

2. They all have the right attitude

3. They’ve all trained hard and consistently for a very long time

Otherwise, he says there is no “magic” program to follow. Foremost, have a plan and have a goal. Pick a sets and rep scheme that’s appropriate to meet your goals and that allows you to make progress from day to day and week to week.

He goes on to say that, when it comes to training, there is nothing new under the sun, so to speak. To illustrate his point, he talks about Georg Hackenschmidt’s The Way To Live In Health and Physical Fitness, published in 1941. In it Georg writes: before you begin a workout session, perform a general warm-up including full mobility work; always eat moderately and drink plenty of water; that bodyweight exercises are good but they won’t get you strong; always use full range of movement when exercising; and rarely go to failure on any set. These recommendations haven’t changed since Hackenschmidt’s time, Wendler points out, and training need not be as complicated as most popular exercise programs make it out to be.

Next, Wendler states that the best motivation is to lead by example. If you fucking practice what you preach, then others will fall in line and do as you do. End. Of. Fucking. Story.

Training should be balanced, front and back, posterior and anterior. In other words, we don’t—or shouldn’t—have favorite muscles when we train.

His final word of advice is to read a little book written by one Mark Rippetoe and one Lon Kilgore: Starting Strength (Wendler says he was “blown away” by it). And since Jim Wendler said you should read it, then you’d better fucking read it. I’ve been recommending it for a while, but, goddamnit, no one listens to the shit that I say. It’s harder to ignore someone with traps the size of Wendler’s, I guess.

I highly recommend that you visit elitefts.com and buy some cool swag and shit from Dave Tate, Wendler and their crew.

Wednesday, September 30, 2009

I caN Haz Cheezburger now?

As I’ve learned a bit more about the “total picture” regarding weight loss and diet, I’ve refined my recommendations a bit.

During a calorie deficit (in order to experience weight loss, you have to expend more calories than you’re putting in, duh!!), it’s important that protein intake be kept high if for no other reason than that protein has a high satiety vs. carbs, which take longer to create that full feeling we’re after and rapidly lead to feelings of hunger again due to the dramatic spike in insulin and subsequent drop in blood sugar you get from consuming them alone or in large quantities. Protein will also help stave off muscle loss when coupled with (relatively) heavy resistance training in the vicinity of 75-85% of your 1 RM for your lifts. Many sources recommend as much as 1-2 grams of protein per pound of bodyweight, but I think this might be extreme. A gram of protein per pound of bodyweight should do for most people, just to be safe.

To estimate maintenance calories, multiply bodyweight times 14-16 calories. Only use sixteen if you’re highly active, fourteen if you’re less so. In order to generate weight loss, subtract no more than 500 calories daily from this number. As little as 200 to 300 calories will probably be enough. I would rather see a slow and steady weight loss of 1 lb.-1 lb. ½ a week than three-five pounds, due to the tendency for folks who lose weight rapidly to gain it back rapidly.

I say no more than 500 calories less daily because any dramatic change that you subject you’re body to will be perceived by it as a stress. Stress generally is bad when it’s high and unrelenting, and stress leads to a catabolic state (state of breakdown rather than build-up) in which cortisol levels remain high. Elevated cortisol means an increased likelihood for the storage of fat and a stunted ability to enhance and/or maintain muscular bodyweight. That’s why I say no more than a 500-calorie deficit daily.

That last point is important and bears repeating since people tend to think more is better when it comes to calorie restriction. There are several important reasons that this just isn’t the case, one of which I’ve already described. Probably the most important is a little thing called basal calories. Your basal calorie limit is the amount of energy that must be consumed in order for your body to carry on its basic functioning even at rest. If those calories aren’t covered, your body will become even stingier with its fat stores, saving them up for a potential crisis. Since we WANT to lose fat, it is important that we reduce calories ENOUGH while still maintaining calories ABOVE that basal limit.

A second but still important reason to keep calorie restriction moderate is that the psychological toll that too few calories takes is too much for some people. The idea of keeping calories dramatically restricted for an indefinite period is overwhelming. Not to mention there are physiological things that happen within the body separate from the psychology involved that can literally make or break your ability to adhere to a diet for the long-term. Extreme calorie restriction coupled with the wrong attitude can and probably will lead to ravenous, overwhelming hunger at some point. This isn’t just a matter of “willpower” only: the body itself sends out impulses that are difficult to deny in cases like these.

A related but different issue is whether to take a diet break every so often. In light of what I’ve said, you should see why taking a break is recommended if you’re going to adhere to your diet for the long-haul. You can experience “burn-out” from extreme dieting, or from dieting too long without breaks, much as you can when exercising at intensities and/or frequencies too high to sustain for periods long enough to see substantial improvement. In fact, if you want to succeed at reaching your weight-loss goals, I’d recommend taking a one-week break from your diet every couple of months.

This last piece of advice may fall on deaf ears since folks who’ve been overweight forever will fear that a diet break may lead to their adopting old habits again. But I’d encourage everyone to allow reason to be the more powerful voice here over fear. Clear, rational thinking coupled with education about the how and why of diet and nutrition should be encouraged in place of self-doubt. Easier said than done, I know.

On a final note, its common practice for diet and nutrition “gurus” to demonize one macronutrient or the other depending on which sort of diet happens to be en vogue among the self-appointed priests of fitness at the moment. Neither the low-fat/high-carb or the low-or-no-carb/high fat camps have it exactly right as they’d have you believe. Suffice it to say, a moderate approach that includes a balance of fat and carbohydrates will suit the majority of people; putting aside variations between individuals for the moment, a diet with enough fat to help keep you satiated (most of it coming from non-saturated sources) and your cells and intestinal tract healthy and happy on the one hand, and with enough carbs to cover the demands of your daily activities on the other, is key. For the sake of ease, a diet that equally divides the fat and carbohydrate calories left over after protein requirements have been met down the middle will work. This is an oversimplification, since variations between individuals could mean that you feel better on a slightly lower or higher carb diet, depending. Also, individuals who engage in regular, prolonged endurance exercise will need more carbohydrates, with the rest of us needing considerably less.

Finally, let’s consider fiber intake for a moment. Fiber is a carbohydrate, but it functions differently than other carbohydrates and has special ramifications for dieters. One type of fiber when consumed becomes like gel in your stomach, slowing gastric emptying. Slowed gastric emptying means you’ll feel fuller longer. Also, fiber is a high-bulk food: it stretches the stomach with the amount of room that it takes up, signaling to you that you’re full. And like protein and fat, fiber slows the rate at which refined carbs are digested and absorbed and how fast they enter the bloodstream, thus preventing that dreaded insulin spike that grabs the sugar from your blood and leaves you feeling sluggish and hungry again. The upshot of all of this is that when you eat fiber, you eat less of other stuff, get fuller sooner and stay fuller longer. And if you’re trying to lose weight, that’s a good thing.

In short keep protein intake high, take in the correct number of calories (neither too many nor too few), don’t be a fat or carb nazi, and eat lots of fiber-containing ruffage, a.k.a. veggies.

Sunday, September 6, 2009

"Teach a man to fish..."

The following is quoted from Matthew Perryman's ebook Maximum Muscle: the Science Of Intelligent Physique Training. Also, please visit Matthew's website at ampedtraining.com.

“Most research into exercise deals with either aerobic exercise or with rehabilitation. As you might gather, this isn't terribly useful for generalizing into strength-training concepts, let alone something specialized like bodybuilding. Although the West is starting to catch up, a lot of what you read about is actually taken from older Soviet-era information, which, while not bad necessarily, can be hard to corroborate.

Once we start to look at the Western research into actual strength exercise, we start to see a common theme: 'untrained subjects'. Now, in some ways this is good because at least it's done in humans. However we run into some potentially major issues because we've seen it demonstrated repeatedly that an untrained person just doesn't respond the same way as someone with years of experience. Lots of strength-training studies will

demonstrate amazing results in untrained subjects, but comparatively few of them account for this so-called 'newbie effect'. Beginners can get away with lots of things; often they will still improve in spite of what they do, not because of it. When we're trying to establish a cause-and-effect relationship, this can throw a huge wrench into things.

It gets worse. The bulk of the research into the actual biochemistry and physiology is done in rats. While there's a lot of similarities in humans and rats, there's a lot of differences too. There's plenty of examples where things that happened in rats didn't pan out in humans; that's a big weakness.

This is a favorite tactic of the supplement industry, actually. They love taking some rat research or weakly applicable research in humans and then claiming it supports their new magic product. They conveniently ignore the fact that not only is that data not applicable, but they also have exactly nothing showing their claimed results in humans. Besides the claims of the product users, of course - but that's not placebo effect or anything. See also my earlier point about controlling for variables; when you don't perform research in controlled conditions, you can't be sure that your attributed cause is creating the effect. Since giving out free supplements to bodybuilders is almost the definition of 'bias' and 'placebo effect', these testimonials have to be considered highly suspect.

And of course all of these objections can apply just as easily to any workout routine, or any study that looks at strength training.”

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)