Part One: Why Strength Train?

Often, physicians and medical professionals cite the benefits of regular, moderate physical activity, particularly the cardiovascular varieties (walking, jogging, biking and swimming, to name a few), but few emphasize the need to strength train. The reasons for this are many, the most likely of which are that cardiovascular training isn’t complicated, doesn’t require special equipment, and isn’t technique-dependent. Medical professionals likely feel that doing something is better than nothing when it comes to physical activity, and less hassle means, odds are, that patients will adhere to a given workout routine for the long term.

But consider that, as we grow older, our ability to carry out everyday physical tasks, such as climbing stairs or lifting heavy objects up and placing them overhead, decreases. Our quality of life depends on the presence of adequate levels of skeletal muscle, the muscle that attaches to our bones and transmits force along them to whatever is being lifted or pushed against, and the ability to recruit these muscles in an efficient, coordinated manner. Cardiovascular training (or “cardio”) does not significantly enhance the size or the quality of the muscles responsible for carrying out everyday tasks. Cardio can improve heart health, but so can strength training, which also greatly improves balance, coordination, strength, and flexibility, when programmed and executed properly.

But what is strength? Put simply, strength is the ability to generate force. Both increased neuromuscular efficiency (which has to do with the way the nervous system “talks” to the muscle) and an increase in size contribute to strength. Strength also depends on the ability of the body to store and quickly replenish energy for the muscles to do their work. When following a properly designed and executed strength training program, you enhance all of these abilities at once.

Part Two: How Do We Strength Train?

The general public regards any training that involves the use of free weights or some other means of external resistance as “strength training.” But while any resistance training program, by definition, must involve some means of applying resistance, strength and conditioning professionals mean something more specific when they use the label “strength training.” Here, it is being used to describe a systematic use of weights to enhance the muscles’ ability to produce force. Using a light weight to perform a large number of repetitions in the range of fifteen or more, for example, does not significantly improve strength because the muscles responsible for the movement are not being made to contract at or near their current maximum force potential. Heavier weights and fewer repetitions are needed in order to make that happen.

For a better understanding, we should conceptualize training in terms of stress and adaptation. When subjected to an unusual stress, our bodies adapt by becoming better at dealing with that stress. If we require our muscles to produce near maximal force by applying resistance to them, then they will respond with an increased force capacity the next time. Provided that we set aside adequate time and energy for recovery between training bouts, strength will increase in an uninterrupted, linear fashion for many weeks and months, if we continue to change the stress—i.e. use progressively heavier loads.

By contrast, using a light weight for a large number of repetitions will primarily enhance muscular endurance, which is a result of an increased ability by the muscle to handle waste products and to store energy, among other things. This is wonderful, but heavier loads utilized across fewer reps can provide a boost to muscular endurance as well (albeit through different mechanisms); and if either a lack of or a decline in strength is limiting you, then much of your time should be spent training in the heavier range anyway. And really, most of us aren’t as strong as we’d like to think we are.

On that note, loads that fall within the range of 75-85% of a person’s current ability to lift will achieve the desired effect. This will mean being able to perform between four and eight repetitions of an exercise before form begins to suffer. As far as exercise selection, we should opt for movements that recruit as much muscle as possible around as many joints as we can, so that a good deal of weight can be used. This should be done over a full range of motion, so that flexibility can be improved and maximum tension is placed on the muscles. Tension is what we’re after. Tension provides mechanical stress, and mechanical stress is what signals the muscle fibers to grow.

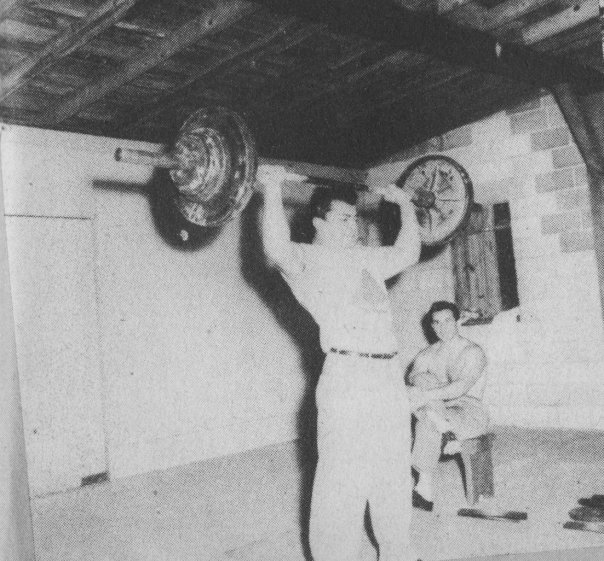

Furthermore, the closer these movements correspond to activities that we’ll be performing in the outside world, the more beneficial they’ll be to us. For this reason, and for those stated above, the barbell back squat, overhead press, deadlift and bench press will form the “backbone” of any effective strength training routine. Now, before anyone—man or woman—should balk at the idea of using barbells, I should explain why barbells are the ideal training implement versus dumbbells, resistance bands or cable machines, to name a few of the alternatives.

Compared to dumbbells, barbells accommodate our need to lift “heavy” weights better because they’re less cumbersome to wield and can be loaded using increments small enough to ensure continual, lengthy progress: whether positioned on our backs or in our hands, barbells are “easier” to handle and allow the trainee to utilize loads nearer to maximum, yet demand a tremendous amount of focus, coordination and stability. This is amply demonstrated by the effort it takes to move a barbell the distance covered by a full-depth back squat, for example. And while machines, cables and resistance bands are less cumbersome even than barbells, they do not require the same level of focus, coordination, stabilization and overall commitment that the barbell does, when supported by the muscles and all of the other skeletal components over the broadest range of motion that still permits good form.

Every workout should include some version of the squat, a pressing exercise and a pulling exercise, so that all of the musculature gets worked in a balanced fashion. For a novice, a full-body barbell routine performed three times a week will make the best use of the trainee’s recovery abilities and optimize his or her growth.

Safety and Efficacy of Barbell Training

Barbell movements, when performed under the watchful eye of an experienced coach, are absolutely safe. Heavy lifting in and of itself is no more injurious than any other rigorous physical activity, and given proper instruction and skillful coaching, heavy barbell training is, in fact, safer. Consider the fact that most folks who train do so without the benefit of an experienced coach or were coached by someone who may or may not have known the proper (i.e. safe) way to execute the movements. If care is taken by the trainee and coach to select loads that are within the current ability of the lifter, and if proper form is utilized, then the risk of serious injury is minimal to non-existent.

Young and old, male and female, dog and cat can safely train in the ways that I’m describing. Both groups will respond to training in much the same fashion, except that older trainees may need more recovery time between training sessions, making a twice-weekly training program more appropriate for some. Male and female trainees will adapt at comparable rates and for roughly the same amount of time on a linearly progressed training regimen.

The general public looks on fearfully at the use of heavy weights. Most believe that training of this kind is harmful to the back and joints. If the load selected matches the trainee’s current ability to lift it, then the muscles around the joints will be handling the load, not the joint surfaces or the ligaments. This is very important to understand. Muscles form a natural “organic brace” around each of the various joints, similar in principle to the orthopedic braces that doctors prescribe for use on patients with knee, ankle or elbow problems. Training these muscles in a balanced fashion around the joints and with the joints held in their mechanically sound anatomical positions makes for healthier joints, if anything. Again, proper weight training leads to healthier joints, not injured joints.

On the subject of youth and adolescent strength training, the National Strength and Conditioning Association (N.S.C.A) recently published an updated position statement that favors vigorous lifting practices, including but not limited to pure strength training of the type outlined above. The paper, entitled “Youth Resistance Training: Updated Position Statement Paper from the National Strength and Conditioning Association,” states:

In general, the risk of injury associated with resistance training is similar for youth and adults. There are no justifiable safety reasons that preclude children or adolescents from participating in such a resistance training program.

To elaborate, the authors note that several studies have found football, wrestling, and gymnastics to be substantially more injurious than resistance training, with the latter comprising only 0.7 percent of 1,576 injuries reported according to one prospective study. Further, the 2005-2006 High School Sports-related Injury Surveillance Study looked at 1.4 million injuries and determined that football had the highest rate of injury, scoring 4.36 injuries per 1,000 “athlete exposures,” as compared to only 0.0013 for resistance training and weightlifting (an Olympic sport). In fact, according to the N.S.C.A., the forces that young athletes encounter on the field or court are “likely to be greater in both exposure time and magnitude” as compared to those encountered while lifting properly.

Within the medical community, fear once existed that resistance training in general could stunt a young athlete’s growth or damage his or her growth cartilage, but to the contrary, the authors of this paper note that “there is no evidence to suggest that resistance training will negatively impact growth” and that “injury to the growth cartilage has not been reported in any prospective youth resistance training research study.”

The authors provide a ringing endorsement for the inclusion of resistance training in youth and adolescent training programs:

Youth resistance training can improve one’s cardiovascular risk profile, facilitate weight control, strengthen bone, enhance psychosocial well-being, improve motor performance skills, and increase ayoung athlete’s resistance to sports-related injuries.

No comments:

Post a Comment